Plagued by a litany of unserviceable sports facilities, trainers with obsolete knowledge, and a lack of constant competition at the grassroots level, Nigeria’s sporting fortunes are ebbing away at great speed. With contemporary athletes now a pale imitation of their predecessors, the exploits recorded by different sports disciplines including athletics, boxing, football, handball, and basketball are distant history. Stakeholders blame the country’s empty trophy chest on, among other things, the failure to sustain efforts made by colonial masters by subsequent administrations, the poor implementation of the National Sports Development Policy, as well as the failure of local councils to pull their weight as far as sports development is concerned. CHRISTIAN OKPARA writes that beyond the development of adequate sports facilities, which will spur children’s interest in sports, there is a compelling need for the re-introduction of competitive sports at the grassroots level, which remains critical in stemming the drift.

Segun Odegbami is one of the biggest names in the African sports community. The Jos, Plateau State-raised former footballer was at one time the best right winger on the continent. It was at a time when most African parents were averse to their wards playing the game.

But Odegbami was known to all, especially for his dazzling runs on the right flank of both the Nigerian national team, Green Eagles and the 1976 Africa Cup Winners Cup champions, Shooting Stars of Ibadan.

Odegbami did not just become a great footballer, he benefitted from a sporting structure that was hardly in prominence then. The 1980 Africa Cup of Nations winner is a product of the grassroots football development programme of the 1960s and early 1970s, whose skill was honed on the facilities built by Nigerian colonial masters and First Republic leaders, who knew the place of facilities in the development of the country’s talented youths.

Reminiscing on his days as a young boy growing up in Jos, Odegbami said: “I started my incursion into sports by playing on the empty streets in Jos as a kid and it was not structured to achieve anything. But my exposure to better sports facilities in my primary and secondary schools (St. Theresa’s Boys’ School, and St. Murumba College – both owned by the Catholic Church and had good Physical Education programmes as extra-curricular activity) that had fairly standard facilities, gave me an early start and edge in development.”

In the colonial days up to the late 1990s, the likes of Odegbami thrived on the availability of sporting facilities where budding athletes were discovered and allowed to hone their skills.

Such facilities as the Bembo Games Village in Ibadan, Nsulu Games Village in Abia State, Afuze Games Village in Edo and the Mambila facility in Taraba State served as the training and camping sites for athletes discovered by dedicated grassroots talent scouts.

Today, these facilities have been abandoned and left to rot by successive administrations, who concentrate on attending competitions rather than developing talents. Some other facilities like the Games Village in Surulere, Lagos (built for the 1973 Africa Games) and the Abuja Games Village (built for the 2003 Africa Games) have been sold to civil servants, who have converted them into residential buildings. The consequence is the lamentable dearth of modern facilities for the myriad of talents that abound nationwide.

Sports facilities of yesteryears

Sports is a big business and a major employer of labour in most countries in the developed world, where it has been elevated to the point that talented youths, mostly from modest backgrounds, leverage their skills to become affluent and well-known personalities in society.

Since such countries are fully aware that sports can be used to boost their economies, they do everything possible, including the provision of required facilities, and a conducive environment for talented men and women to develop their skills.

In colonial Nigeria, the administrators recognised the place of sports in human development, hence conscious efforts were made to provide standard sporting facilities across the country.

Beyond that, they also encouraged regional, district, and municipal authorities to create spaces and build arenas for the citizens, especially schoolchildren, who were often drawn to these arenas without prompting by teachers to begin their first steps in sports.

From the early days of independence up until the late 1970s, successive governments improved the facilities that they inherited from the colonialists, with almost every state boasting a central sports stadium for local and national events.

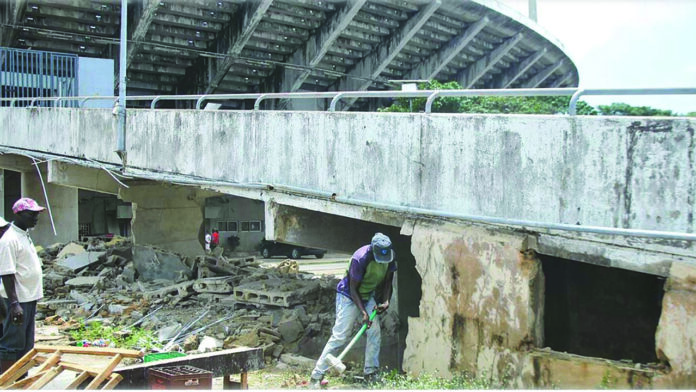

A section of the abandoned Gokana Township Stadium, Rivers State.

The introduction of the National Sports Festival in 1973 to advance the post-Nigeria Civil War principle of “no victor, no vanquished,” further bolstered the number of sporting facilities as each host state usually built new facilities and a games village for the festival, which later became their camping facility ahead of major local and national competitions.

However, from the turn of the late 1980s, things started to change with successive governments paying scant attention to sports development, even as some “misguided” officials saw sports as mere recreation, while those who did not understand the relevance of some facilities converted them to other uses.

Across the country lie several sports facilities that have been converted to other uses by officials, who felt that such facilities would serve the country’s needs better in other areas than in sports.

From empirical observation, most residential estates built in the colonial era and by the succeeding administrations had areas mapped out for sports, and other recreational activities.

A typical example of an estate with sporting facilities designed by the founders, which has now been abused is FESTAC Town in Lagos, which was built for the African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC) in 1977, by the Gen. Yakubu Gowon-led administration.

FESTAC had areas designated for sports, with almost every road boasting a basketball court. Unfortunately, in the late 1980s, military officers who oversaw the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) started selling some plots of land, including those designated for sports to developers, who built houses and shops on them.

Thus, FESTAC Town, which had been converted into a modern residential estate for middle-class workers lost its essence and gradually became a ghetto of sorts, with all manner of structures replacing the sporting facilities.

There are many other examples of well-planned sports facilities, which have been converted to other uses by government officials, who appear not to understand the rationale behind, or importance of such structures. The situation has been worsened by the inability of local councils (which are the first point of contact with budding talents in their formative years) to provide facilities for sports in their areas.

Again, unlike in the past when primary and secondary schools had dedicated sporting facilities, most schools, especially privately owned ones only engage in serious sporting activities in the build-up to the yearly inter-house competitions, which are hosted in hired facilities outside the schools.

According to experts, the availability of proper sporting facilities provides budding talents the opportunity to hone their skills and take their first step toward becoming competitive.

They noted that good infrastructure also attracts top talent and creates opportunities for athletes to compete at a high level, adding that the country has the potential to produce world-class athletes, but without proper infrastructure, that potential will remain untapped.

Dr Odegbami, who is now one of Africa’s strident voices in sports and youth development, believes that Nigeria can only get back to the glory days of the early independent years when its leaders make concrete efforts to provide facilities for talented youths to hone their skills.

He said: “Facilities are the key to development. Without them, there cannot be development of sport to a high level. The quality of the facilities is the next in line of importance; the better the quality of the facilities for training, the better the quality of athletes that will be produced.”

According to the former national team captain, development never happens in a vacuum. “The last level is facilities for competition… this takes development to the highest level, of course, and makes competing at the highest level meaningful, and success achievable.”

The National Stadium, Lagos, has been shut for repairs for over five years.

Odegbami believes Nigeria can regain its lost spot at the top of African sports if the leaders go back to the system that served the country so well in the past.

He said sports are needed in the country’s educational development agenda for all youths, adding that getting back to that era must be pursued with vigour and seriousness.

“It is the will to do it that has been lacking, as well as a lack of full appreciation and understanding of the impact sports can have in the overall development of a child outside of academics.

“Reviving the culture of basic facilities at the grassroots, particularly in schools and local government council environments, can be done very easily and at little cost when compared to the damage being done by their lack of the sports development of young boys and girls in society.”

North: Gone are the days of sports centres, playgrounds

Kano State’s Commissioner for Youths and Sports Development, Kabiru Ado Lakwaya, said in a recent report that the Northern region has been lagging behind the South for too long because the region lacks facilities, qualified personnel and adequate competition. He said, “If you are talking about sports development you are talking about the three parameters: personnel, facilities and competition.

“Facilities take 70 to 85 per cent of sports development. But if you look at the whole North, we don’t have enough facilities to accommodate the different games. For instance, we have only two standard swimming pools in Kaduna and Bauchi states. The remaining 17 states in the North have no swimming pool. How can we develop swimming in these states?

“In athletics, only a few states in the North have standard tracks. You can find tracks in states like Kano, Bauchi, Benue and Kaduna. If there is a competition in athletics, how do you think the North would fare?”

The Captain of the U-17 national team to the first FIFA Cadet World Cup in China, which Nigeria won in 1985, Nduka Ugbade, believes that sports began gasping for breath since those in authority started neglecting the provision and maintenance of facilities at the grassroots.

Lagos State has an estimated 1,010 public primary schools and 670 public senior secondary schools, but most of these schools lack basic sports infrastructure, while the few private schools with decent facilities are not open to children from outside their schools.

A recent report showed that public and private schools must provide evidence of the existence of multipurpose fields before they are given a license to operate in Lagos State.

“For primary schools, there must be a demarcated playground filled with white sharp sand, or a playground covered with artificial grass carpet; outdoor learning resources for nursery classes, and five outdoor resources (play gadgets).”

But Ugbade, who benefitted from the grassroots development programme of the late 1970s and early 1980s, said such guidelines are hardly adhered to these days.

The ex-international, who is the head coach of Nath Boys, a grassroots football team owned by sports enthusiast, Yemi Idowu, said that Nigeria would only get it right if it returned to the system that served the nation so well in the past.

Ugbade said: “When we were growing up, there were playing grounds all over Lagos State, where children played during break periods, and on non-school days. Then, we had games masters, and physical education teachers, who taught us the basics of many sports.

“I learnt the three stages of football development playing with my friends after school. These three stages prepare youngsters for contact with the real ball.

“For instance, if you were able to master the control of the rubber ball- felele, and the hard plastic ball, you would do anything with the real ball when you start playing with them. This control you learn playing on the street corners, or at the back of your house with your mates. Children these days are unfortunate that they don’t have the privilege of going through rough times.

“Again, the lack of facilities drives children away from sports to other things. They need facilities to acquaint themselves with sports and hone their talents, even without trained coaches. Most unfortunately, a good number of the facilities have been built on; schools no longer have playing grounds where children can play twice a day while in school as was done in those days.

“Such stars as Henry Nwosu and the late Stephen Keshi became international football stars while still in secondary schools because their schools had well-maintained football pitches, and there were policies that allowed them to combine their studies with sport.

“This is no longer possible these days. Segun Odegbami and Adokie Aimiesiamaka were internationals while still in tertiary institutions, but today, any university student who pays too much attention to sports risks incurring the wrath of lecturers and getting bad grades.”

Ugbade also lamented that the country is facing a dearth of well-trained game masters who know how to introduce children into sports properly. These, he said, have resulted in many children learning sports the wrong way at an early stage.

“When I was growing up, I played football, trained in boxing, and also played handball. We had Cuban boxing coaches, who taught children the rudiments of boxing. These were coaches on an exchange programme that was organised by the Federal Government.

“Do you know that Yemi Tella, who led Nigeria to the U-17 World Cup title in South Korea in 2007, was my handball coach? When I was in secondary school, he taught us handball and led the state’s handball team. Such was the calibre of coaches we had in secondary schools in those days.”

Ugbade lamented that some administrators, who benefitted from the system laid down by colonial and post-colonial leaders have done nothing to maintain or replicate such programmes.

A tale of abandoned facilities in Southeast

Former Enyimba of Aba defender, Ikechukwu Ogbonna, equally accused local councils of failing to play their part to help the country keep pace with her contemporaries, sports-wise. He further alleged that local councils are so hamstrung that they hardly have money for developmental projects.

“Most of these local council chairmen were hand-picked by their state governors, who also commandeered the councils’ allocations from the Federal Government, and released to them peanuts to take care of their overhead costs.

“In such situations, these councils don’t have money to build sports facilities in their areas, while some state governments do not have such facilities on their list of priorities,” he said.

Across the Southeast, Ogbonna said, many facilities built by the colonial administration and governments that came immediately are now obsolete after being left to rot by successive administrations.

He said: “Dr Sam Mbakwe built the Grasshoppers Handball Stadium, and the Dan Anyiam Stadium in Owerri, in the1980s, but these facilities have been left to decay by his successors.

“The Grasshoppers Stadium was the best of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa when it was built, in the 1980s. It helped Grasshoppers Handball Club to rule Africa for several years. But if you go there now, it is in such a sorry state that you will not believe that it once hosted Africa’s biggest championships.

“For over two years, the Nnamdi Azikiwe Stadium, Enugu, has been locked to athletes because of its bad state. This stadium has hosted many world championships, including FIFA U-20 and U-17 World Cup competitions.

“If you visit the Nsulu Games Village, you will cry because that edifice built as a camping site for national and international athletes in the 1970s has been overtaken by weeds. I hear soldiers have converted it to their camp.

“All over Igboland, you will find relics of what used to be sports facilities littering everywhere and when you have governors, who still see sports as recreation, then you realise that we are still far from the journey to recover our lost position in sports,” he stated.

The Nnamdi Azikiwe Stadium, Enugu, houses handball, badminton, volleyball, athletics, and basketball. There are no standard courts for lawn tennis, while boxing, karate, and judo are provided for marginally, as there are no advanced, or extraordinary facilities provided for them.

A visit to the judo training facilities in the Enugu State Sports Council showed a complete lack of the basic needs for judo training. Judokas train in one big room, and on old and torn judo mats.

A coach-athlete at the facility noted that most sports in the state thrive on the ingenuity or know-how of individual athletes, and not because they had any kind of standard facilities to train with. Currently, athletes, including tennis players, train with facilities offered by associations like the Enugu Sports Club.

Ogbonna said that the solution to the challenge lies in empowering private individuals and corporate bodies to invest in sports, adding that in most developed countries, sports are managed by the private sector while the government provides the enabling environment.

“I like what some young Nigerians are doing with football and basketball. We have Remo Stars, Doma United, Sporting Lagos, and FC Ifeanyi Ubah with their facilities.

“Remo Stars have a sporting complex that is as good as any you will find in the developed world. FC Ifeanyi Ubah has a stadium in Nnewi, while Sporting Lagos and Doma United are developing their structures.

“In the South East, we have some private facilities like the Rojenny Sports Complex, and Nanka Stadium, in Anambra State; there are such facilities in Abiriba, Item, and Ohafia, in Abia State, while Ebonyi developed some structures during the last regime.

“Governor Alex Otti’s plan to take over and rehabilitate the Nsulu Games Village is a welcome development. But the governor and others in the Southeast should also look at ways of training officials, who will scout and develop talents at the grassroots.

“State commissioners for education and sports should also be encouraged to work together to develop schools’ sports because that is where the future talents and stars can be found.”

Former African tennis champion, Dr Sadiq Abdullahi, who benefitted from playing in the facilities littered all over the Obalende area of Lagos growing up, said the apathy to sports development shown by most of the local councils have contributed to the dearth of sports facilities across the country.

He said the local councils through the sports councils are not designed properly to identify, nurture, and expose talented players. Many reasons account for this. Two of the reasons are government funding and hiring good coaches and paying them well. Most of the councils, he said, do not have the funds to build the basic facilities needed to attract children to sports. Abdullahi said that the facilities and playgrounds left by the colonial masters were sustained until the late 1980s by various governments.

“The decay started at the local councils in all of the states because there were no allocations to this level of government to maintain them. The little funds appropriated were misappropriated. Corruption at the state level by civil servants and politicians, a tendency by state governments to seize their funds for social and capital development. Even when the funds get to them, corruption is another killer monster,” he said.

Where are the budding stars?

Interestingly, Lagos and other southern states are faring better than the North in terms of the provision of sporting facilities, as most Northern governors appear to see no reason to invest in sports infrastructure.

Aside from owning football clubs, many states in the North have made little or no efforts at all to develop other sports disciplines or create an enabling environment for children to hone their skills.

States like Kano, Plateau, Kaduna, Benue, and Nasarawa are exceptions as they put conscious efforts into raising teams for national competitions. This does not apply to states like Borno, Bauchi, Gombe, Kebbi, and Sokoto, among others that hardly feature in discussions that centre on sports development.

Sokoto and Benue states ended the last National Youth Games in Asaba without a single medal. Gombe State, which featured on the podium, was not originally billed to be at the Games until its athletics association chairman, Shaibu Gara-Gombe, decided to sponsor the state’s athletics team to the festival.

This is a state that has failed to feature in the yearly Milo Secondary Schools Basketball Championship for many years because “the government failed to release funds for such a venture.”

The North is blessed with abundant talents, who are only waiting to be discovered and nurtured to stardom, but the lack of opportunities, and the right environment to bloom have troubled the region for so long.

These factors, to a reasonable extent, explain why national teams in most sports are dominated by athletes from the southern part of the country.

Ironically, while the North does not produce many national athletes, it has the highest number of sports administrators at the national level.

Underscoring the importance of standard facilities to sports development, a former director of sports at Kano State Sports Commission, Dr Bashir Ahmad Maizare, said that the country cannot produce world-class athletes without world-class facilities, adding that the country lacks even elementary facilities needed by children in their formative years.

He said: “We no longer produce world-class athletes because there are no more regularly organised intramural and extramural sports competitions within and outside the school system.

“There are no constant yearly school sports competitions at both local and state levels, and there are no constant national annual school sports competitions at different levels. Above all, therefore, are no harnessed athletics sports programmes in the country for the future champions.”

He explained that the National Sports Development Policy spells out the role of each arm of government in facilities and sports development, adding that its implementation has been the bane of the sector.

“This policy was adopted in 1989, and reviewed in 2018, and 2021 respectively. There is also a guide for implementing this National Sports Development Policy in the country, as well as a guide for policymakers and implementers.

“The policy described and illustrated the roles and functions of the Federal Government, states, local councils, institutions/schools, corporate bodies, individuals/philanthropists and sponsors/foreigners,” he said.

According to him, the solution to poor facilities and low levels of the country’s sports development lies in the “provision and adoption of a bill at different levels that protect and stop the conversion of playing grounds for commercial or residential purposes.”

He continued: “We must plan and construct future schools with sports infrastructure at different levels; update the unserviceable sports facilities to avoid unnecessary encroachment by the public, and ensure constant use of sports facilities for both training and competitions in our schools.”

Beyond the provision of appropriate and adequate sporting facilities, Akintokunbo Adejumo is of the view that a strategic synergy and partnership between sports and education remains one of the surest ways of arresting sports decline in the country.

In his paper “Grassroots Sports Development: Towards the Rejuvenation of School Sports in Nigeria, he advised the sports and education ministries to find a way to ensure that the school curriculum has at least three hours of physical education (PE) per week in it.

“Physical Education (PE) teachers and games masters in schools should be engaged in talent identification, especially education in primary schools and junior secondary schools. There must be a strategic synergy and partnership between the sports and education agencies at the state and federal levels. Every state sports ministry/commission must have a functional school sports department.

“Introduction of an effective scouting system to work in talent identification at primary and grassroots levels,” he said must be taken seriously, adding that proper training of youth coaches must be given priority as not every coach that can work at school and grassroots levels.

Additionally, the “grading and classification of coaches is essential. Different qualities and expertise of coaching education required for the three stages of school/grassroots sports development, and the provision of sports facilities in schools and communities.”

He suggested that there could be a need to include the availability of sports facilities as a criterion for registering new primary and secondary schools, adding that the authorities should work closely with private schools, which usually have sports facilities, and use these as training hubs for other schools in the neighbourhood.

A former chairman of Owan West Council of Edo State, Frank Ilaboya, blames sports’ dwindling fortunes on a lack of modern facilities and a weak policy that has failed to address the country’s sports needs.

For the country to regain its place among the top sporting nations of the world, according to Ilaboya, the government has to re-introduce competitive sports at the grassroots levels.

“I think what the present Edo State government is doing is close to what I am advocating. Governor Godwin Obaseki is pushing for grassroots participation by building stadiums across the 18 local councils of the state.

“The Edo State Sports Commission, under the chairmanship of ex-Olympian, Yusuf Alli has been mandated to produce 10,000 athletes from the grassroots level. Such policy, if followed up by the next government, will ensure that the kids at the grassroots levels are busy all year round, and in a short while from now, things will begin to change.

“It is not rocket science… The late Dr Samuel Ogbemudia did it so well when he was the administrator of the old Bendel State. I think we can do it again, but my worry has been the inconsistency in policy formulation and implementation. Each government wants to do something different by discarding the previous administration’s policies.”

Ilaboya advocated a sports policy backed by consistent evaluation, saying: “The truth of the matter is that the raw talents that abound at the grassroots level are waiting to be harnessed and honed. But we should start by training the trainers using modern tools because sports are technically driven.

“The government must provide basic facilities and possess the strong will to implement existing policy on sports development.”He also called for a policy that would make it compulsory for local councils across the country to devote part of their budgets to facility development. “It should not be a matter of choice, but a matter of compulsion. This is where a national policy backed up by a strong will to get results comes in.

“I am expecting the Ministry of Sports to come up with an articulate policy in this direction. The ministry has been trimmed to focus only on sports development, unlike the previous dispensation when it was also saddled with youth development.

“The current minister, Senator John Owan Enoh, should, as a matter of urgency, come up with a policy framework for this direction,” he said.